不可能三角

HILLEL THE ELDER, a first-century religious leader, was asked to summarise the Torah while standing on one leg. “That which is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow. That is the whole Torah; the rest is commentary,” he replied. Michael Klein, of Tufts University, has written that the insights of international macroeconomics (the study of trade, the balance-of-payments, exchange rates and so on) might be similarly distilled: “Governments face the policy trilemma; the rest is commentary.”

初世纪的宗教领导独腿长者希勒尔曾经被要求总结律法,他回答道:“己所不欲,勿施于人,这便是整个律法,其它的一切都是注脚。”塔夫茨大学的迈克尔·克莱因曾写道:国际宏观经济学(研究贸易,国际收支平衡,汇率等的学科)也可以类似地被精炼成一句话:“政府面临政策困境;其它的都是注脚。”

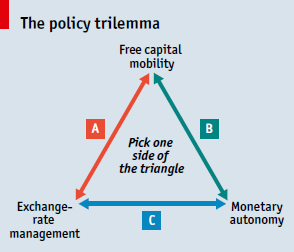

The policy trilemma, also known as the impossible or inconsistent trinity, says a country must choose between free capital mobility, exchange-rate management and monetary autonomy (the three corners of the triangle in the diagram). Only two of the three are possible. A country that wants to fix the value of its currency and have an interest-rate policy that is free from outside influence (side C of the triangle) cannot allow capital to flow freely across its borders. If the exchange rate is fixed but the country is open to cross-border capital flows, it cannot have an independent monetary policy (side A). And if a country chooses free capital mobility and wants monetary autonomy, it has to allow its currency to float (side B).

政策困境也被称为不可能或者不稳定三角,意思是一个国家必须在资本自由流动,汇率管理和货币政策独立性之间做出选择(图中三角形的三个顶点)。三者之间只能选其二。若一国想要固定其货币价值并且使自己的利率政策免受外界影响(三角形的C边),那么它就不能允许资本自由流动。如果一国实行固定汇率但是开放资本流动,那么它将失去货币政策独立性(A边)。如果一国选择资本自由流动并且想要货币独立性,那它必须实现浮动汇率(B边)。

To understand the trilemma, imagine a country that fixes its exchange rate against the US dollar and is also open to foreign capital. If its central bank sets interest rates above those set by the Federal Reserve, foreign capital in search of higher returns would flood in. These inflows would raise demand for the local currency; eventually the peg with the dollar would break. If interest rates are kept below those in America, capital would leave the country and the currency would fall.

为了理解这个困境,想象一个国家将本国货币与美元汇率固定并且对外国资本开放。如果其央行设定的利率高于美联储的,那么追逐高回报的资本就会流入。这些资本流入会使得对本币的需求增加,最终使得与美元的挂钩崩溃。如果利率低于美国,那么资本会流出使得本国货币贬值。

Where barriers to capital flow are undesirable or futile, the trilemma boils down to a choice: between a floating exchange rate and control of monetary policy; or a fixed exchange rate and monetary bondage. Rich countries have typically chosen the former, but the countries that have adopted the euro have embraced the latter. The sacrifice of monetary-policy autonomy that the single currency entailed was plain even before its launch in 1999.

当限制资本流动是不合需要或者徒劳的时候,这个三难困境就归结为一个选择:浮动汇率和货币政策独立性;或者固定汇率和货币政策非独立。富裕国家倾向于前者,而欧元区的国家则选择了后者。单一货币会牺牲货币政策独立性,这点即使在1999年其实行之前就显而易见。

In the run up, aspiring members pegged their currencies to the Deutschmark. Since capital moves freely within Europe, the trilemma obliged would-be members to follow the monetary policy of Germany, the regional power. The head of the Dutch central bank, Wim Duisenberg (who subsequently became the first president of the European Central Bank), earned the nickname “Mr Fifteen Minutes” because of how quickly he copied the interest-rate changes made by the Bundesbank.

在实际运行中,一些机智的成员国将他们的货币与德国马克挂钩。因为资本在欧洲境内自由流动,三难困境迫使准会员国们保持货币政策与当地一霸——德国保持一致。于是荷兰央行的行长Wim Duisenberg(他最终成为了欧洲央行的第一任行长)获得了“十五分钟先生”的外号,因为他总是迅速照搬德意志联邦银行设定的利率。

This monetary serfdom is tolerable for the Netherlands because its commerce is closely tied to Germany and business conditions rise and fall in tandem in both countries. For economies less closely aligned to Germany’s business cycle, such as Spain and Greece, the cost of losing monetary independence has been much higher: interest rates that were too low during the boom, and no option to devalue their way out of trouble once crisis hit.

这种货币上的农奴制对于荷兰是可以忍受的,因为它的商业与德国关系密切并且商业状况这两国之间是串联的关系。但是对于经济状况与德国的商业周期不那么一致的国家(比如西班牙和希腊)来说,失去货币政策独立性的代价就高得多了:利率在经济增长时过低,在经济危机的时候却不能降低来应对困境。

As with many big economic ideas, the trilemma has a complicated heritage. For a generation of economics students, it was an important outgrowth of the so-called Mundell-Fleming model, which incorporated the impact of capital flows into a more general treatment of interest rates, exchange-rate policy, trade and stability.

与许多伟大的经济观点一样,三难困境也有一个复杂的遗产。在一代经济学学生的记忆中,三难困境是蒙代尔弗莱明模型的自然产物,它整合了在一个更一般化的利率处理,汇率政策,贸易和稳定性的模型中,资本流入的影响。

The model was named in recognition of research papers published in the early 1960s by Robert Mundell, a brilliant young Canadian trade theorist, and Marcus Fleming, a British economist at the IMF. Building on his earlier research, Mr Mundell showed in a paper in 1963 that monetary policy becomes ineffective where there is full capital mobility and a fixed exchange rate. Fleming’s paper had a similar result.

该模型以此命名来表示对蒙代尔(一个聪明的年轻加拿大贸易理论学家)和弗莱明(IMF的一个英国经济学家)在19世纪60年代早期发表的论文的认同。蒙代尔在他之前研究的基础之上,于1963年发表的论文中指出,货币政策在完全资本流动和固定汇率时失效。弗莱明论文有着类似的结果。

If the world of economics remained unshaken, it was because capital flows were small at the time. Rich-world currencies were pegged to the dollar under a system of fixed exchange rates agreed at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944. It was only after this arrangement broke down in the 1970s that the trilemma gained great policy relevance.

如果世界的经济一直保持稳定,那只是因为资本流动在当时很小。富裕世界货币在布雷顿森林体系(1944)中都与美元挂钩实行固定汇率。直到19世纪70年代随着该体系的瓦解,三难困境才得到政策关注。

Perhaps the first mention of the Mundell-Fleming model was in 1976 by Rudiger Dornbusch of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dornbusch’s “overshooting” model sought to explain why the newish regime of floating exchange rates had proved so volatile. It was Dornbusch who helped popularise the Mundell-Fleming model through his bestselling textbooks (written with Stanley Fischer, now vice-chairman of the Federal Reserve) and his influence on doctoral students, such as Paul Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld. The use of the term “policy trilemma”, as applied to international macroeconomics, was coined in a paper published in 1997 by Mr Obstfeld, who is now chief economist of the IMF, and Alan Taylor, now of the University of California, Davis.

也许是麻省理工的Rudiger Dornbusch在1976年第一次提及蒙代尔弗莱明模型的。Dornbusch的“夸张”模型想要解释为什么新兴地区的浮动汇率政策是不稳定的。正是Dornbusch通过他的畅销教科书(与现任美联储副主席史丹利费舍尔合著)以及他对博士生(比如保罗克鲁格曼和茅瑞斯·奥伯斯法尔德)的影响使得蒙代尔弗莱明模型被人们熟知。被应用于国际宏观经济学的术语——“政策的三难困境”是由奥伯斯法尔德(现任IMF首席经济学家)和阿伦泰勒(现在加州大学任教)在1997年的一篇论文中发明的。

But to fully understand the providence—and the significance—of the trilemma, you need to go back further. In “A Treatise on Money”, published in 1930, John Maynard Keynes pointed to an inevitable tension in a monetary order in which capital can move in search of the highest return:

This then is the dilemma of an international monetary system—to preserve the advantages of the stability of local currencies of the various members of the system in terms of the international standard, and to preserve at the same time an adequate local autonomy for each member over its domestic rate of interest and its volume of foreign lending.

但是为了完全理解这个三难困境的远见和重要性,你需要往前追溯更远。在1930年出版的《货币论》中,凯恩斯指出当资本自由流动时矛盾是不可避免的:

当时是国际货币系统的困境:根据国际标准,保留本币稳定的好处 VS 与此同时保留各国对其利率和外国借贷量的足够的自主性。

This is the first distillation of the policy trilemma, even if the fact of capital mobility is taken as a given. Keynes was acutely aware of it when, in the early 1940s, he set down his thoughts on how global trade might be rebuilt after the war. Keynes believed a system of fixed exchange rates was beneficial for trade. The problem with the interwar gold standard, he argued, was that it was not self-regulating. If large trade imbalances built up, as they did in the late 1920s, deficit countries were forced to respond to the resulting outflow of gold. They did so by raising interest rates, to curb demand for imports, and by cutting wages to restore export competitiveness. This led only to unemployment, as wages did not fall obligingly when gold (and thus money) was in scarce supply. The system might adjust more readily if surplus countries stepped up their spending on imports. But they were not required to do so.

这是首次对政策困境的浓缩,虽然资本流动被视为理所当然。凯恩斯早在1940年代当他思考战后全球贸易如何重建的时候就敏锐地发现了这一点。凯恩斯认为固定汇率有利于贸易。他强调,一战二战之间的金本位制的问题在于它不可以自动调节。如果类似于1920年代的大量贸易不平衡建立,贸易赤字过就不得不流出黄金。于是它们提高利率来抑制进口需求并且通过降低工资来恢复出口竞争力。这仅仅导致了失业,因为当黄金(货币)减少供给的时候工资不应减少。如果贸易盈余国增加进口额那么这个系统就能更加迅速地调整。然而他们并没有被要求这么做。

Instead he proposed an alternative scheme, which became the basis of Britain’s negotiating position at Bretton Woods. An international clearing bank (ICB) would settle the balance of transactions that gave rise to trade surpluses or deficits. Each country in the scheme would have an overdraft facility at the ICB, proportionate to its trade. This would afford deficit countries a buffer against the painful adjustments required under the gold standard. There would be penalties for overly lax countries: overdrafts would incur interest on a rising scale, for instance. Keynes’s scheme would also penalise countries for hoarding by taxing big surpluses. Keynes could not secure support for such “creditor adjustment”. America opposed the idea for the same reason Germany resists it today: it was a country with a big surplus on its balance of trade. But his proposal for an international clearing bank with overdraft facilities did lay the ground for the IMF.

相反,他提出了另一个框架,这在之后成为了英国在布雷顿森林体系中的谈判地位的基础。国际清算银行将会保证造成贸易盈余或者赤字交易的平衡。框架中的每个国家都在ICB中有透支贷款,额度与其贸易额相匹配。这将使得赤字过在金本位制下能够负担的起调整的费用。对于过于宽松的国家会有处罚:例如,透支额会计增长利息。凯恩斯的框架也会惩罚通过对于过量贸易盈余收税囤积的行为。凯恩斯不能保证这种“信贷调整”会获得支持。美国反对的理由与今天德国反对的理由如出一辙:他们都是贸易盈余大国。但是他对于有透支贷款国际清算银行的提议为后来的IMF奠定了基础。

Fleming and Mundell wrote their papers while working at the IMF in the context of the post-war monetary order that Keynes had helped shape. Fleming had been in contact with Keynes in the 1940s while he worked in the British civil service. For his part, Mr Mundell drew his inspiration from home.

弗莱明和蒙代尔在IMF工作的时候写下了他们的论文,当时还处于凯恩斯主张的战后货币秩序中。在英国行政部门工作时,弗莱明一直与凯恩斯保持着联系。而蒙代尔确实从自己的家乡获得的启发。

In the decades after the second world war, an environment of rapid capital mobility was hard for economists to imagine. Cross-border capital flows were limited in part by regulation but also by the caution of investors. Canada was an exception. Capital moved freely across its border with America in part because damming such flows was impractical but also because US investors saw little danger in parking money next door. A consequence was that Canada could not peg its currency to the dollar without losing control of its monetary policy. So the Canadian dollar was allowed to float from 1950 until 1962.

在二战之后的几十年间,资本流动的快速增长超过了经济学家们的想象。之前资本流动一方面受到管制,但也受到了投资者谨慎心理的约束。加拿大却是个例外。资本在加拿大和美国之间的流动一方面因为堵住流动是不现实的,另一方面因为美国的投资者们认为将资金放在加拿大没什么风险。后果就是加拿大在保证货币政策独立性的同时不能将货币与美元挂钩,所以加元与美元汇率在1950至1962年之间允许浮动。

A Canadian, such as Mr Mundell, was better placed to imagine the trade-offs other countries would face once capital began to move freely across borders and currencies were unfixed. When Mr Mundell won the Nobel prize in economics in 1999, Mr Krugman hailed it as a “Canadian Nobel”. There was more to this observation than mere drollery. It is striking how many academics working in this area have been Canadian. Apart from Mr Mundell, Ronald McKinnon, Harry Gordon Johnson and Jacob Viner have made big contributions.

像蒙代尔这样的加拿大人在想象当资本自由流动和浮动汇率时国家面临的权衡时,具有得天独厚的优势。当蒙代尔获得1999年诺贝尔经济学奖的时候,克鲁格曼开玩笑说这个奖是“加拿大的诺贝尔”。这句话在单纯的幽默之余也有着深层的思考。在这个邻域的学者们,加拿大人的比例高到令人惊异的地步。除了蒙代尔,罗纳德·麦金农、戈登约翰逊和雅各布·维纳都曾做出巨大贡献。

But some of the most influential recent work on the trilemma has been done by a Frenchwoman. In a series of papers, Hélène Rey, of the London Business School, has argued that a country that is open to capital flows and that allows its currency to float does not necessarily enjoy full monetary autonomy.

但是近来最有影响的关于三难困境方面的研究都出自一位法国女性之手。来自伦敦商业学院的埃莱娜雷伊在一系列的论文中指出,在一个对资本开放以及浮动汇率的国家,其不一定享有完全的货币政策独立性。

Ms Rey’s analysis starts with the observation that the prices of risky assets, such as shares or high-yield bonds, tend to move in lockstep with the availability of bank credit and the weight of global capital flows. These co-movements, for Ms Rey, are a reflection of a “global financial cycle” driven by shifts in investors’ appetite for risk. That in turn is heavily influenced by changes in the monetary policy of the Federal Reserve, which owes its power to the scale of borrowing in dollars by businesses and householders worldwide. When the Fed lowers its interest rate, it makes it cheap to borrow in dollars. That drives up global asset prices and thus boosts the value of collateral against which loans can be secured. Global credit conditions are relaxed.

雷伊的分析开始于她对风险资产价格(例如股票,高收益债券)的观察,这些资产的价格运动银行信贷宽松和全球资本流动总量的变化高度一致。对于雷伊来说,这样的协同运动恰恰反映了“全球金融循环”由投资者对风险的偏好驱动。反过来这些运动也受到美联储货币政策的强烈影响,美联储拥有全世界商业和个人美元借贷总量的控制权。当美联储降息时,借入美元变得便宜,这会拉升全球资产价格进而使得贷款担保品的价格上升。全球信贷环境就会放松。

Conversely, in a recent study Ms Rey finds that an unexpected decision by the Fed to raise its main interest rate soon leads to a rise in mortgage spreads not only in America, but also in Canada, Britain and New Zealand. In other words, the Fed’s monetary policy shapes credit conditions in rich countries that have both flexible exchange rates and central banks that set their own monetary policy.

相反地,在雷伊近期的研究中,她发现美联储预期之外的加息不仅仅提高了美国的抵押贷款息差,加拿大、英国和新西兰的也被拉高。换句话说,美联储的货币政策对富裕浮动汇率和拥有货币政策独立性的国家的信贷环境也有影响。

A crude reading of this result is that the policy trilemma is really a dilemma: a choice between staying open to cross-border capital or having control of local financial conditions. In fact, Ms Rey’s conclusion is more subtle: floating currencies do not adjust to capital flows in a way that leaves domestic monetary conditions unsullied, as the trilemma implies. So if a country is to retain its monetary-policy autonomy, it must employ additional “macroprudential” tools, such as selective capital controls or additional bank-capital requirements to curb excessive credit growth.

粗读这个结果你会认为政策的三难困境实际上是一个两难选择:开放资本流动 VS 对本国金融环境的控制。事实上,雷伊的结论更加微妙:浮动的汇率并不会像三难困境中说的那样将资本流动调整到使本国货币环境不受影响的程度。因此,如果一国保持自己的货币政策独立性,它必须使用额外的“宏观审慎”工具,例如选择性的资本管制或者额外的银行资本金要求来限制信贷的过量增长。

What is clear from Ms Rey’s work is that the power of global capital flows means the autonomy of a country with a floating currency is far more limited than the trilemma implies. That said, a flexible exchange rate is not anything like as limiting as a fixed exchange rate. In a crisis, everything is suborned to maintaining a peg—until it breaks. A domestic interest-rate policy may be less powerful in the face of a global financial cycle that takes its cue from the Fed. But it is better than not having it at all, even if it is the economic-policy equivalent of standing on one leg.

从雷伊的研究中我们可以明确的一点就是,全球资本流动的巨大力量意味着浮动汇率国的货币政策独立性比三难困境中说的受到更多的限制。也就是说,浮动汇率并不像固定汇率一样具有限制性。在经济危机中,所有的资产都想维持一个挂钩——直到维持不下去。在全球金融周期在美联储后面亦步亦趋时,国内的利率政策就不那么管用了。但是,至少有比什么都没有好,即使这是相当于一条腿站立的经济政策。